Labor shortage of 6.44 million workers: four proposed solutions (labor market projections for 2030)

Release Date:

※This article is a machine translation.

Labor shortages. News stories about labor shortages are reported daily to such an extent that it would not be an exaggeration to say that there has not been a day in years when we have failed to see or hear this term discussed in the media. Labor shortages today raise the question of whether convenience stores and supermarkets can continue to maintain twenty-four-hour operations but, for several years now, operating hours and store-opening plans have had to change in a slew of cases because of the lack of manpower, thereby forcing companies to respond. In collaboration with Professor Masahiro Abe of the Faculty of Economics at Chuo University, we estimate that Japan will have a shortage of 6.44 million workers by 2030 and, accordingly, propose specific measures to address this shortage.

Index

- The worsening shortage of workers: a forecast of a shortage of 6.44 million workers by 2030

- Increase the number of working women: prevent workers from leaving their jobs due to childbirth and childcare by improving childcare services

- Increase the number of senior workers: Create conditions and environments that are easy to work in, and encourage people to work without age restrictions

- Increase the number of foreign workers in Japan: Improve the appeal of Japan as a place to work, and maintain the pace of expansion in the number of people accepted

- Increase productivity: Improve productivity through automation using AI and IoT, and reduce labor demand

- “Knowing the possibilities of the future allows us to consider countermeasures early on” – that is the significance of these estimates

The worsening shortage of workers: a forecast of a shortage of 6.44 million workers by 2030

The estimates were based on two assumptions: firstly, the government’s estimate that real GDP will remain at 1.2% (*1), and secondly, the population estimate that the Japanese population will be 116.38 million by 2030 (*2). In response to the large-scale labor shortage of 6.44 million people revealed by the estimates, there are only two possible directions for measures: “increasing the supply of labor” and “reducing the demand for labor”.

With regard to the supply of labor, in Japan, where the aging population is progressing rapidly, there is no prospect of an increase in the number of young workers for the time being. The new labor force that is expected to fill the gap is women and senior workers who are currently not working because their conditions do not match the requirements, etc. First, let’s consider how we can increase the number of working women.

※1: Cabinet Office “Medium- to Long-term Economic and Fiscal Projections (submitted to the Council on Economic

and Fiscal Policy on January 23, 2018)”

※2: National Institute of Population and Social Security

Research ‘Projected Population of Japan (2017)’

Increase the number of working women: prevent workers from leaving their jobs due to childbirth and childcare by improving childcare services

According to the “Monthly Report on the 2017 Population Movement Statistics (Overview of Annual Totals (Approximate Numbers))” by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the average age of mothers at the time of their first childbirth in 2017 was 30.7 years old. For women who give birth at this age, their 30s and 40s fall right in the middle of the child-rearing period. On the other hand, when looking at the labor force participation rate by age, the rate drops particularly in the 30s, forming what is known as the “M-shaped curve”. There are various possible factors that cause the M-shaped curve, but one of the most significant is probably the impact of women leaving the workforce due to childbirth and childcare.

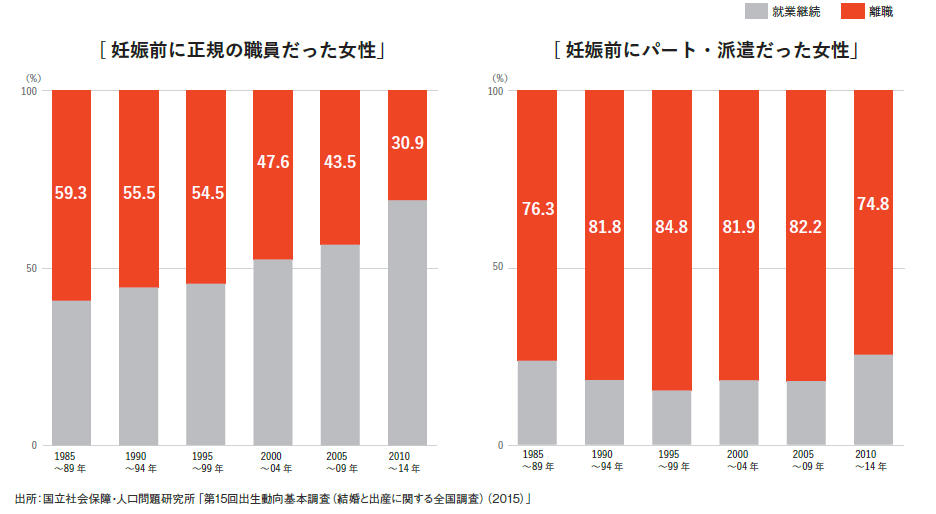

According to the 15th Japanese National Fertility Survey conducted by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the employment rate of women who had their first child between 2010 and 2014 was 53.1%. Even now, when it is said that the use of maternity and childcare leave is progressing and the number of women working while raising children is increasing, half of working women are still leaving their jobs after having a baby. Furthermore, if we look at women who were employed part-time before becoming pregnant, 74.8% (Figure 1, right) quit their jobs after having a baby. The high rate of part-time workers leaving their jobs may be due to the fact that, compared to full-time workers, systems such as maternity and childcare leave are not well developed, and working hours are shorter, which puts them at a disadvantage when it comes to using childcare facilities. In order to prevent this kind of job loss, it is necessary to develop systems and environments that allow women to continue working while raising children.

Figure 1: Employment status of women by employment status before first pregnancy

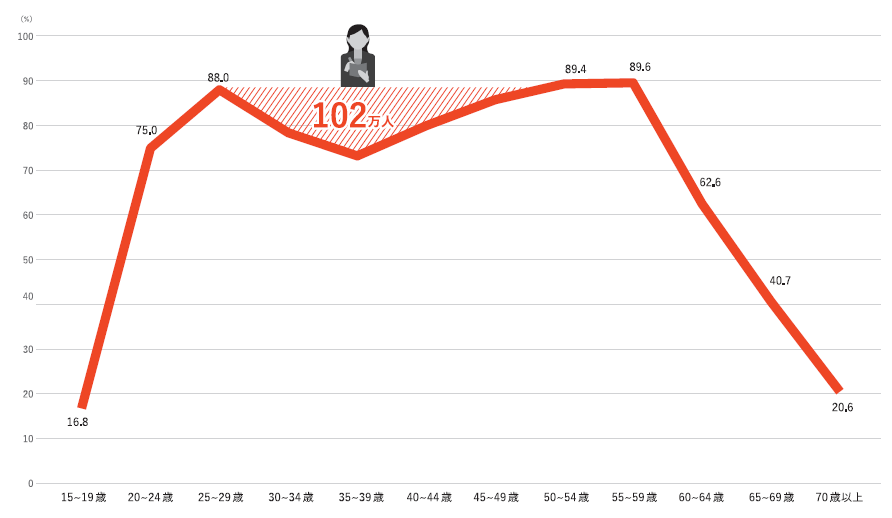

If we assume that all of the factors contributing to the M-shaped curve are due to the lack of childcare support, then how many women would be able to work again if childcare support were improved? We therefore calculated the number of women in the labor force (Figure 2) if the labor force participation rate of 88.0% for women aged 25 to 29, before the M-shaped curve began, continued without decreasing until age 49. The number is 1.02 million.

Figure 2: Female labor force participation rate in 2030 and the expected increase in the number of

working women

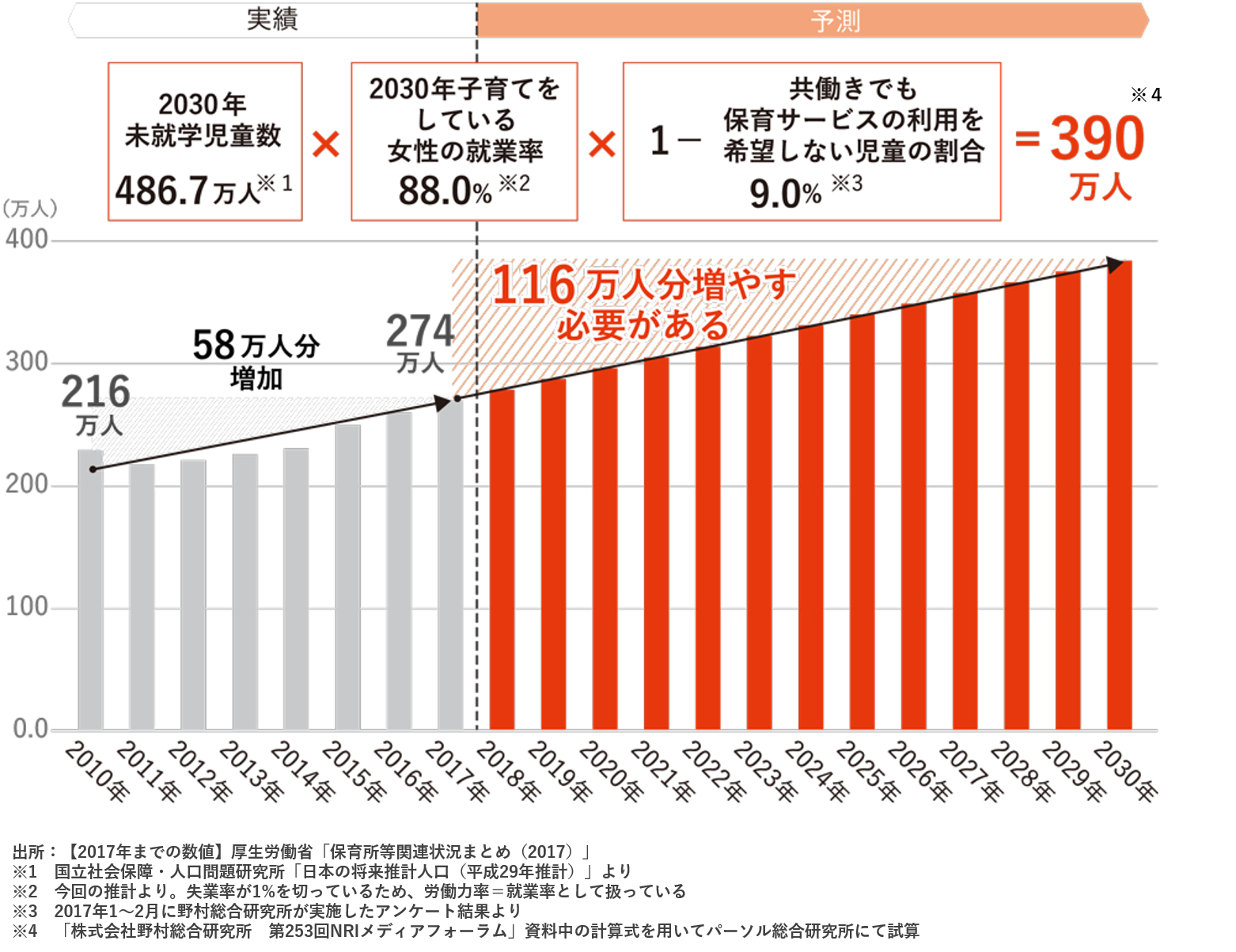

Furthermore, based on the above assumptions, we also calculated the number of childcare places needed to maintain the labor force participation rate (88.0%) of women aged 25 to 29 until they reach 49 years of age. We found that, excluding cases where grandparents provide support, 3.9 million places would be needed (Figure 3). Although the government and local authorities are continuing to improve childcare services, further efforts are expected to increase the number of women in the workforce.

Figure 3: Actual and projected capacity of childcare facilities

Interview with an expert on how to increase the number of working women

“Both the government

and companies should be looking to women who want to take on the challenge of both work and child-rearing as

‘regular human resources’.(Japanese version)”

Ms. Kana Takeda, a senior consultant at the Nomura Research

Institute’s Center for the Future, points out that increasing the number of childcare places available could help

mothers who want to have another child to have their second or subsequent child, and could therefore increase the

birthrate. We spoke to her in more detail.

Increase the number of senior workers: Create conditions and environments that are easy to work in, and encourage people to work without age restrictions

Next, let’s take a look at senior workers. First, looking at the employment situation based on the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s “Labour Force Survey”, in 2018, 57.9% of men and women in their 60s were working. Since hitting bottom in 2004, the number has increased year on year, with the number of women in particular increasing by around 1.5 times compared to 2004. If the trend of increasing participation in the workforce by seniors continues, how many more seniors are likely to be active in the labor market by 2030?

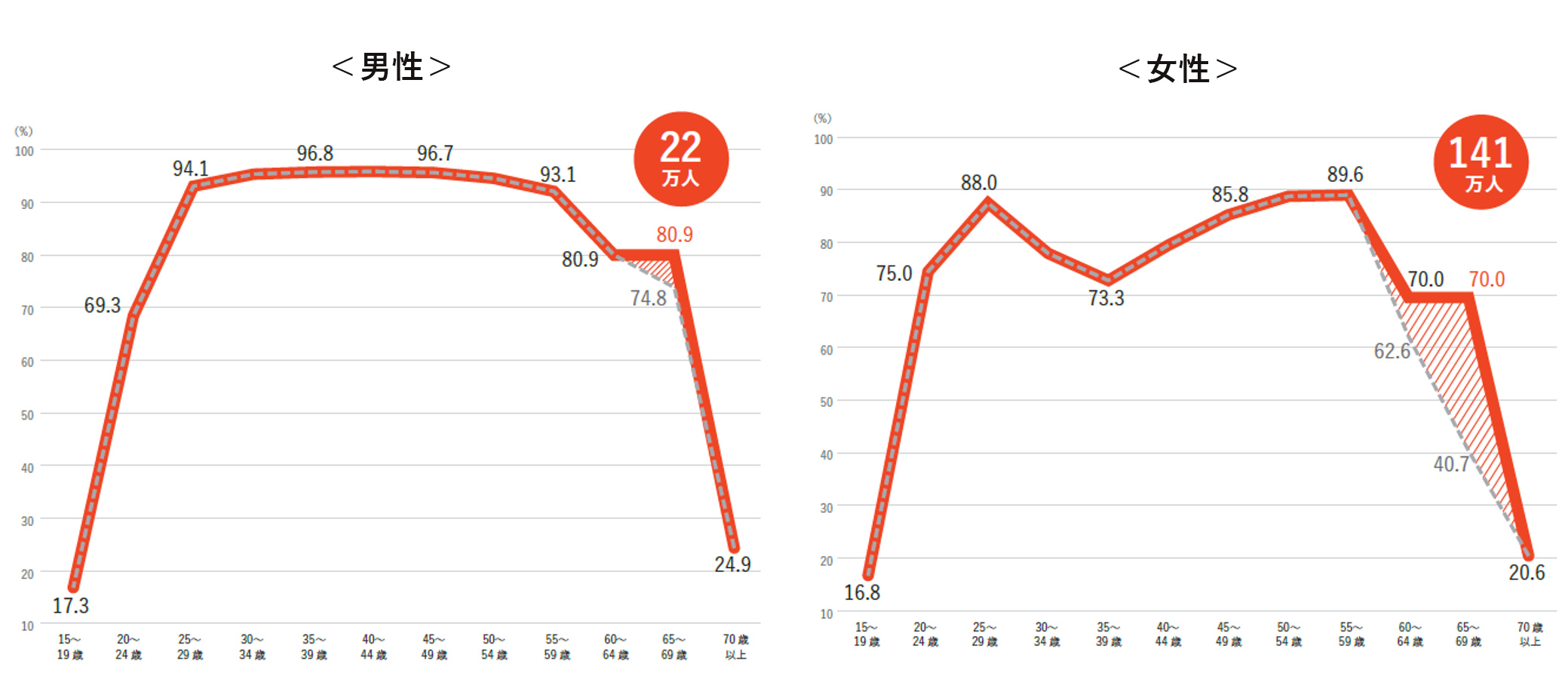

We therefore estimated the following figures for men and women respectively. For men, more than 90% of them are still working until the age of 59, and it is expected that the labor force participation rate will remain high in the future, so we considered the case where the labor force participation rate of those aged 65 to 69, for whom the labor force participation rate drops sharply, is increased. Specifically, this is the case where the labor force participation rate of 80.9% (estimate for 2030) at the age of 64 is maintained until the age of 65 to 69. As few women are employed after the age of 60, and the labor force participation rate for women aged 60 to 64 was expected to be 62.6% and for those aged 65 to 69 40.7% in 2030, we considered the case where at least 70% of women aged 60 to 69 started working. As a result, it was found that an increase of 220,000 men and 1.41 million women (Figure 4) could be expected.

Figure 4: Labor force participation rate in 2030 and the number of senior workers expected to

increase

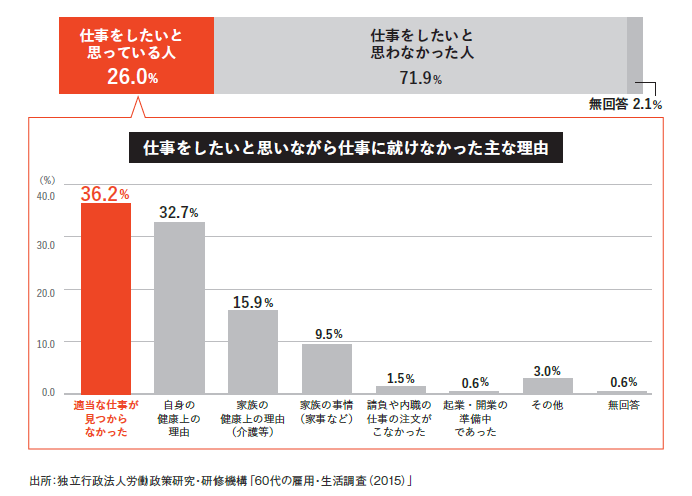

However, this result is limited to the case where seniors who are not currently working are able to find work as they wish, and in reality, not all seniors who want to work are able to find work as they wish, even now. In the “Employment and Livelihood Survey of People in Their 60s (2015)” conducted by the In the “Employment and Livelihood Survey of People in Their 60s (2015)” conducted by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, an independent administrative corporation, 44.5% of the respondents were so-called “unemployed” people who were not working and earning an income, and of these, 26.0% wanted to work. The main reason given for not being able to find work despite wanting to work was “I couldn’t find a suitable job” at 36.2% (Figure 5). The survey also asked respondents to give details of the reasons why they had not been able to find suitable work. The most common reason given was “I’m not picky about my conditions, but there’s no work available” (37.6%), followed by “The type of work didn’t match my preferences” (36.1%) for men, and “The working hours didn’t match my preferences” (25.2%) for women. On the other hand, when those who answered that they “couldn’t find a suitable job” were asked about their preferred way of working, the highest response was “I want to be employed by a company etc. on a part-time basis” at 50.1%.

Figure 5: Percentage of those aged 60-69 who want to work and reasons for not working

For seniors who are willing to work but are unable to find employment, it is important to create working conditions, hours and environments that are easy to work in. In order to get the 1.63 million seniors (both men and women) who are not currently working to become new workers, it will be necessary to take measures not only for those who are looking for work, but also to encourage those seniors who do not want to work (who make up 70% of the unemployed) to find employment.

Interview with an expert on “How to increase the number of senior workers

”Seniors who think ‘I

want to continue contributing to society as an active member for my whole life’ are a treasure of Japan.(Japanese

version)”

Aiming to achieve a “society where people can work throughout their lives”, Professor Hiroko

Akiyama of the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Gerontology, who has been involved in 30 years of follow-up

surveys and social experiments, points out that employment is effective for seniors to continue living

independently. We asked her what the government, local governments and companies should do to achieve a society

where seniors can work with vitality.

Increase the number of foreign workers in Japan: Improve the appeal of Japan as a place to work, and maintain the pace of expansion in the number of people accepted

In terms of securing new labor, there is high social expectation for women, seniors, and foreigners. In particular, with the establishment of the new residence status “Specified Skills (1 and 2)” in the revised Immigration Control Act (Immigration Act) passed in December 2018, the acceptance of foreign workers has expanded in 14 industries, including nursing care, food service, agriculture, and construction.

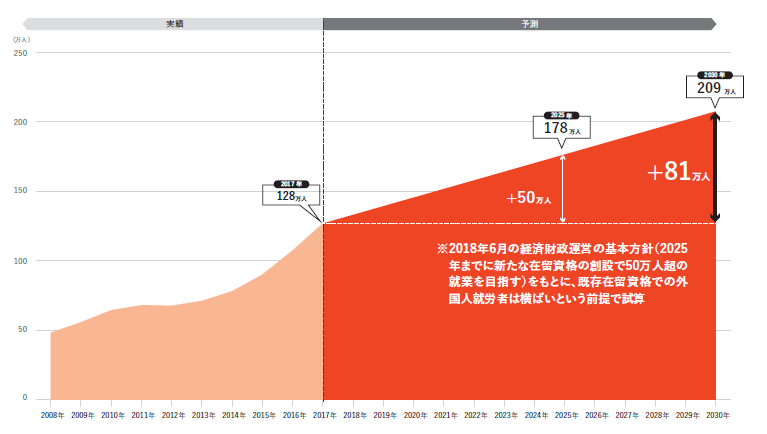

Figure 6 shows the number of foreign workers in Japan in 2030, based on government policy, assuming that the number of foreign workers with existing status of residence remains the same. The government policy that was used as a reference when making the estimate was the Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform in June 2018, which aims to create new resident statuses by 2025 to bring in over 500,000 foreign workers (after the estimate was made, a new policy was announced in November 2018 aiming to bring in a maximum of 340,000 foreign workers over five years from 2019, when the revised law comes into effect)

Figure 6: Changes in the number of foreign workers up to 2030

However, it is important to note that these estimates are based on the assumption that foreign nationals want to work in Japan. Even if the door is opened to foreign nationals through new residency statuses, etc., it is not clear whether they will choose Japan as a place to work. This is because the problem of a shortage of manpower due to the aging population is no longer a problem that only Japan faces in Asia. In addition, many countries are seeing improvements in their treatment of workers, such as rising wages due to significant economic growth, and the competition to acquire labor from these countries is only going to intensify in the future. In order to reach the target number of people accepted, it is necessary to make continuous efforts to improve the appeal of Japan as a place to live and work, so that foreigners will want to live and work here.

Interview with an expert on “How to Increase the Number of Foreigners Working in Japan”

“Harnessing the

abilities and diversity of foreign nationals for the development of companies and cities(Japanese

version)”

In Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka Prefecture, nearly 3% of the population are foreign nationals. More

than 80% of these foreign nationals have long-term resident status, and the city is becoming increasingly settled.

Mr. Yasutomo Suzuki, the mayor of Hamamatsu City, who has “aimed to coexist with foreign nationals as citizens, not

as workers”, talks about the points that the national government, local governments and companies should focus on in

the future when accepting foreign nationals.

Increase productivity: Improve productivity through automation using AI and IoT, and reduce labor demand

So far, we have calculated the expected increase in the number of women, senior workers and foreign workers (1.02 million women + 1.63 million senior workers + 0.81 million foreign workers = 3.46 million in total) from the perspective of how we can increase the number of workers in response to the estimated shortfall of 6.44 million workers in 2030. However, in order to theoretically eliminate the shortfall of 6.44 million people, an additional 2.98 million people’s worth of labor force must be secured.

In order to further reduce the labor shortage, we will also have to consider reducing the demand for labor itself. The current estimates take into account the trend of productivity improvements to date, but do not necessarily factor in the effects of dramatic technological innovation. It is hoped that the dramatic automation brought about by the use of AI and RPA (Robotic Process Automation) will reduce the demand for labor by 2.98 million people. The minimum level of productivity improvement required at this time would be around 4.2%, which corresponds to 2.98 million of the 70.73 million jobs that need to be filled. But is this really possible?

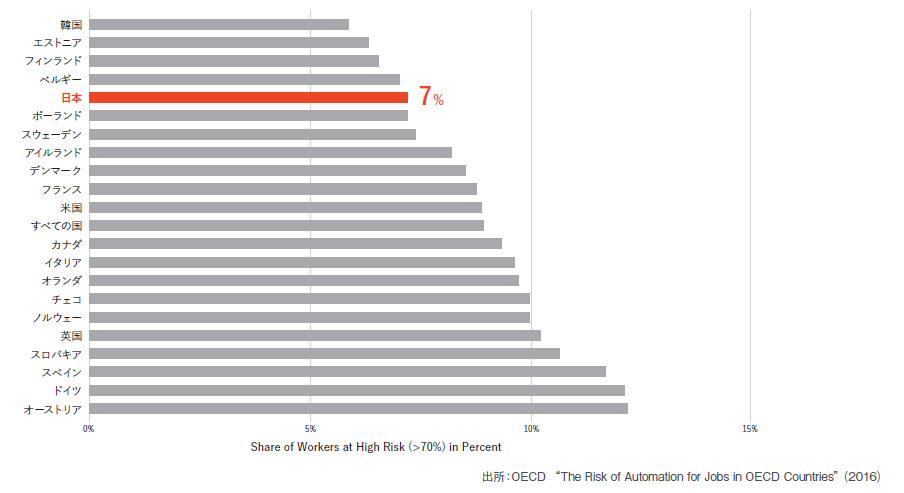

As a reference, let’s take a look at the estimates published by the OECD in 2016. Figure 7 shows the results of estimates of the percentage of workers in OECD countries who are employed in jobs that have the potential to be automated for more than 70% of their tasks. In Japan, it is estimated that more than 70% of the work currently carried out by 7% of the workforce will become unnecessary due to automation in the future. In other words, a productivity increase of 4.9% (7% x 70%) is expected. If automation progresses as estimated by the OECD, the problem of a shortage of 2.98 million workers, which is a concern in the current estimates, may be resolved.

Figure 7: Percentage of workers in jobs with high potential for automation (OECD countries)

Interview with an Expert on “How to Increase Productivity”

“The total number of

workers will remain largely the same due to AI and IoT, but employment polarization and economic disparity will

increase(Japanese version)”

Koichi Iwamoto, a senior researcher at the Japan Productivity Center, points out

that the development of AI and IoT will bring about major changes in the employment structure. What should

individuals and companies do to prepare for the transformation of the employment structure brought about by

mechanization? We spoke to him about the latest research trends surrounding the mechanization of labor.

““Knowing the possibilities of the future allows us to consider countermeasures early on” – that is the significance of these estimates

What will the labor market of the future actually look like? Whether or not the current estimates of a shortage of 6.44 million workers in 2030 are correct, whether or not the number of workers will really increase by 1.02 million women, 1.63 million seniors, and 810,000 foreign workers, and whether or not a 4.2% increase in productivity will be achieved, we won’t know until 2030. However, by presenting estimates of a possible future, it may be possible to consider countermeasures from an early stage and find ways to prevent the situation from worsening. What can companies do now to prepare for the 6.44 million shortage? In addition to interviews with experts on various themes, the HITO REPORT also includes an interview with Professor Abe, who participated in the joint research, so please take a look.

Interview with Professor Masahiro Abe, Faculty of Economics, Chuo University

What should we be

doing to avoid the future of a “labor shortage of 6.44 million people”?(Japanese version)

We hope that readers will also be able to make use of these estimates in considering various measures in their own workplaces.

*This column is an excerpt from the “HITO REPORT vol.4 Future Estimates for the Labor Market 2030” publication.

For more details, please see below.

HITO REPORT vol.4 Future Labor Market Projections to 2030(Japanese version)

A shortage of 6.44 million workers – proposals for four solutionsAt present, Japan is facing an unprecedented shortage of labor. However, the specific shortage figures are not clear, and this is not leading to any countermeasures. Therefore, Persol Research and Consulting has used a “forecasting model” developed in collaboration with Professor Masahiro Abe of the Faculty of Economics at Chuo University to estimate the supply and demand situation for labor in 2030.

Read the PDF

THEME

注目のテーマ

CONTACT US

お問い合わせ

こちらのフォームからお問い合わせいただけます