How an organizational culture in which adults continue to learn (learning culture) should be fostered: Based on a fact-finding survey on relearning targeting middle-aged and senior workers

Release Date:

※This article is a machine translation.

The trinity of labor market reforms promoted by the government encourages the movement of labor into growth sectors and emphasizes the support provided for the development of abilities and skills through the process of reskilling. In today’s business environment, labor shortages have given rise to serious business continuity issues and the introduction of generative AI and other examples of new digital technology is also accelerating. The government policy in this area is exceedingly important for companies and for workers seeking to adapt to these changes. However, an international survey that we conducted in 2022*1 revealed that Japanese workers are far less growth-oriented than workers in other countries and that investments in personal education are also inadequate. Therefore, this column focuses on the actual conditions and perception of re-learning*2 especially among middle-aged and senior workers between the ages of thirty-five and sixty-four years and on the points of involvement by companies. We would like to explore the ways companies might go about improving employee motivation to learn based on the results of a quantitative survey administered to 9,000 middle-aged and senior workers by the authors of this column*3.

*1 Persol Research and Consulting “Global

Employment Status and Growth Awareness Survey (2022)”

*2 re-learning; continuing to learn about work and

careers outside of work

*3 Persol Research and Consulting + Hiromichi Saito Laboratory, Sanno University “Quantitative Survey on

Learning and Working Lives of Middle-aged and Senior Workers”

Index

- The reality of middle-aged and senior workers’ re-learning

- The existence of biases that prevent adults from learning

- Stirring up a sense of crisis for no reason will not lead to action in adult learning

- Summary: Turning learning into action and making the results an asset for the organization

- Conclusion

The reality of middle-aged and senior workers’ re-learning

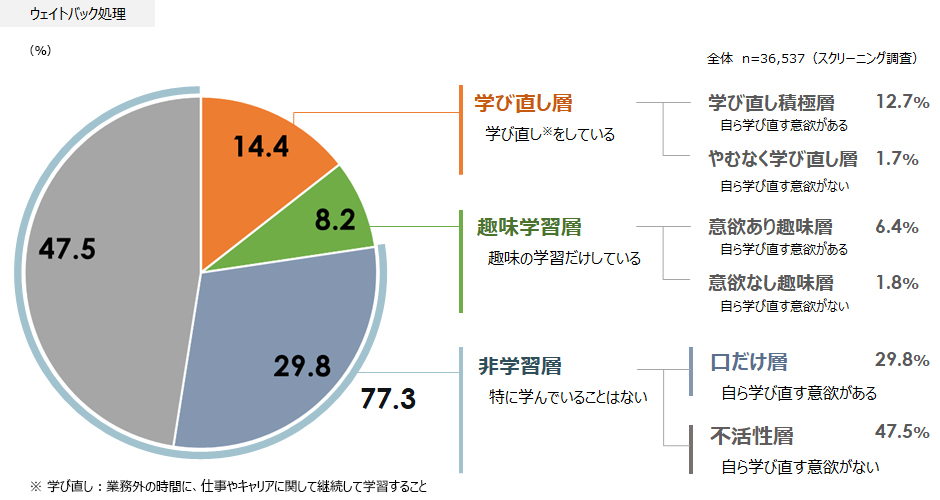

The survey results showed that 70% of middle-aged and senior workers felt that “it is an age when you need to keep learning no matter what your age”, and 63% thought that “re-learning is useful for your future career”. On the other hand, the percentage of people who were actually re-learning was only 14.4%, and it was confirmed that 77.3% were not engaging in re-learning (Figure 1). Of those who are not taking any action to retrain, 29.8% felt that they needed to retrain in some way, but the most common reasons given for not taking action were “I don’t have the time” and “I don’t have the money”. Other common reasons given were “I don’t know what to study” and “I don’t know how to study”.

However, the people who are actually re-learning are more likely to be those who work long hours, and while the average annual learning budget is 100,000 yen, the average actual expenditure is 30,000 yen. The reason why people who understand the need to take action to re-learn but are unable to actually do so give the answers “I don’t have time” and “I don’t have money” is thought to be a problem with the prioritization of resource allocation for learning in time outside of work, and suggests a low motivation to learn.

Figure 1: Percentage of middle-aged and senior workers who are re-learning

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Saito Laboratory, Sanno University, “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

The existence of biases that prevent adults from learning

There are a number of complex factors behind the low motivation to learn among Japanese workers, so it is important to be careful not to over-simplify the issue, but what the authors focused on in the survey results was the existence of biases such as attitudes towards learning. 70% of respondents thought that “the best way to learn about work is to learn it on the job”, and 45.6% also felt that “learning about work outside of work hours is unlikely to lead to performance improvement”. This is a “workplace bias” towards relearning.

Figure 2: Middle-aged and senior workers’ attitudes towards relearning [workplace bias]

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Saito Laboratory, Sanno University “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

In addition, 46.4% of those who were studying again thought that “training and acquiring qualifications is

what studying is”, and 37.8% thought that it was something that you do quietly at a desk, showing a “desk-bound,

self-study bias”. Perhaps studying again is often seen as something narrow, like cramming for exams when

you were at school or as part of vocational training for new recruits.

In addition, there was also a “time performance bias”, where people want to learn quickly and “want to feel the results of their learning immediately” (60.4%), and a “status quo bias”, where people have managed to get by without having to relearn anything (Figure 3). There was also a deep-rooted “secret study bias” that made people feel that there was an atmosphere of not talking about what you were studying (56.2%), highlighting the impact of organizational culture and climate that makes it difficult for adults to find the joy and significance of learning itself.

Figure 3: Middle-aged and senior workers’ attitudes towards relearning [time performance bias]

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Saito Laboratory, Sanno University, “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

Stirring up a sense of crisis for no reason will not lead to action in adult learning

So, how can we encourage middle-aged and senior workers to take action in their learning? We looked for clues from three perspectives: organization (job), supervisor, and individual. First, from the perspective of job, there seems to be a high correlation between “job expertise” and relearning. Workers who felt that their job expertise was low were more likely to feel the need to relearn, especially those who felt a strong sense of crisis about their future (Figure 4). However, those with low job-related expertise were actually not doing much relearning (Figure 5).

On the other hand, more than half of those who felt they had high job-related expertise, whether they felt a strong sense of crisis about the future or not, felt the need to relearn, and they were doing so to an equal degree. In other words, needlessly stirring up a sense of crisis about the future (although it may be possible to arouse a sense of the need to relearn) will not lead to action, and it is suggested that other factors such as the “need to guarantee a high level of expertise” will have an impact on taking action.

Figure 4: The impact of career anxiety on the desire to retrain [by level of expertise]

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Saito Laboratory, Sanno University, “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

Figure 5: Career anxiety x retrain type [by level of expertise]

* “Re-learning” group: people who are re-learning, “hobby learners” group: people who are only learning for their hobbies, “talking only” group: people who have the motivation to re-learn but are not doing anything in particular, “inactive” group: people who have no motivation to re-learn and are not doing anything in particular

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Sato Laboratory, Sanno University “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

The next point of focus was “supervisor behavior”. It was confirmed that when the supervisor themselves are

proactive about learning related to their work, their subordinates are more likely to be influenced and become

proactive about relearning. It is not difficult to imagine that the positive words and actions of the supervisor

towards learning can promote the learning motivation of their subordinates. If the North Wind stirs up a sense of

crisis and encourages learning, then the positive behavior of a superior towards learning acts like the sun,

encouraging their subordinates to be proactive in their learning.

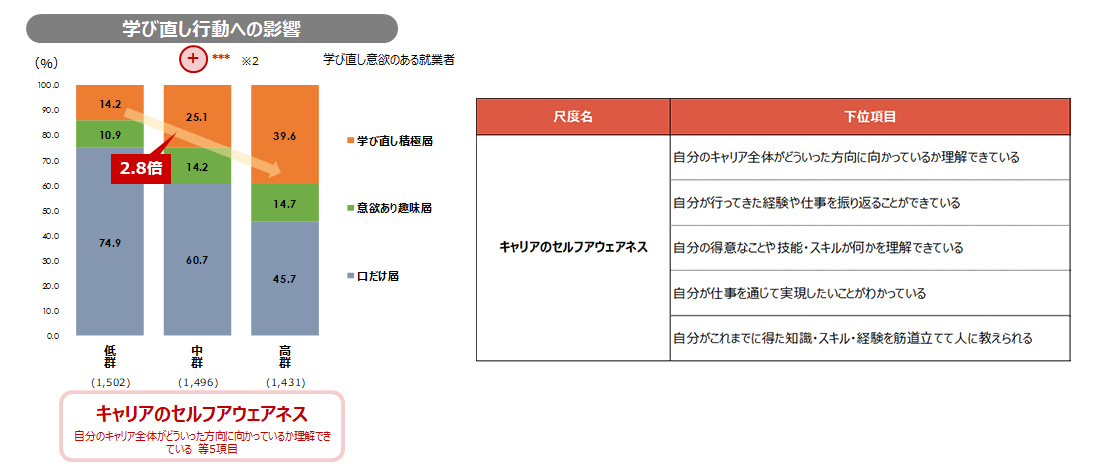

Next, we looked at “career self-awareness” (internal self-awareness) in individuals. Self-awareness is the act of being aware of and deeply understanding one’s own emotions, strengths and weaknesses, desires and impulses. Self-awareness of one’s overall sense of direction in one’s professional career can be said to be a state of having a clear sense of the past, present and future in one’s professional life, and a high level of internal understanding of oneself. It was confirmed that the group with high self-awareness of their career was 2.8 times more likely to be proactive about re-learning than the group with low self-awareness.

Figure 6: The impact of self-awareness of one’s career on re-learning behavior

Source: Persol Research and Consulting + Saito Laboratory, Sanno University, “Quantitative Survey on Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Learning and Working Life”

Summary: Turning learning into action and making the results an asset for the organization

From the results discussed so far, the following points were identified as being important for turning employees’ learning into action and making the results of that learning an asset for the organization

1. A bias in the way we view learning and a workplace culture that discourages learning can inhibit adult

learning

2. Raising awareness of the need to prepare for future career challenges is not enough

to encourage adults to learn again

3. Employees who consider themselves highly specialized in

their work are more likely to learn again

4. If their superiors are enthusiastic about learning

again, their subordinates are also more likely to learn again

5. Employees with a high level of

self-awareness of their careers are proactive about “re-learning”

From these points, it is important to first promote self-development among the executive and managerial levels, and to create opportunities to communicate this to those around them. In doing so, it is important to not limit the content or methods of learning, and to have the executive and managerial levels happily talk about what they are learning from even content that was previously considered to be a “hobby”. This will help to create an organizational culture and climate in which learning is seen as a positive thing, and a positive attitude towards diverse learning will become more widespread.

Furthermore, it is thought that providing employees with opportunities to improve their self-awareness of their careers, and seeking higher levels of expertise through the redesign of their current duties, will also contribute to improving their motivation to learn. In this context, it will be important to incorporate the perspectives of job enrichment and job enlargement, given that new technologies such as generative AI will become more prevalent in the workplace in the future.

If an organization encourages (and allows) its employees to learn in a variety of ways, and makes use of the results of that learning as an asset of the organization without keeping them secret, it will be in a position to create a virtuous cycle of investment and visualization of human capital, which is the aim of human capital management. The human resources department of a company is expected to play an important role in leading the creation of a “learning culture”.

Conclusion

I would like to think of “adult learning” as something that you do actively and enjoy, cultivating knowledge and lessons that are meaningful to you, rather than studying for exams or compulsory education and training that you had to do as a student. It’s a bit like traveling. A trip (or business trip) that you go on because someone told you to and you don’t want to go on might be troublesome and painful, but a trip that you go on because you’re interested in it is fun. Whether it’s taking it easy and resting, enjoying new discoveries as you walk around a strange town, or chatting happily with friends, even the hardships of sudden rain or long-distance travel might seem like fun. The experiences you have there will be remembered with some kind of meaning, and they will probably have an impact on your way of thinking and behavior afterwards. It’s fine to go around checking out famous tourist spots on the shortest route with a guidebook in hand, but there are many different ways to enjoy a trip. In the same way, I’d like to think that adult learning is also diverse.

I hope that this column will be of help in the discussion of re-learning for middle-aged and senior workers.

THEME

注目のテーマ

CONTACT US

お問い合わせ

こちらのフォームからお問い合わせいただけます

![Figure 2: Middle-aged and senior workers' attitudes towards relearning [workplace bias]](/assets/individual/thinktank/assets/20240325_column_02.jpg)

![Figure 3: Middle-aged and senior workers' attitudes towards relearning [time performance bias]](/assets/individual/thinktank/assets/20240325_column_03.jpg)

![Figure 4: The impact of career anxiety on the desire to retrain [by level of expertise]](/assets/individual/thinktank/assets/20240325_column_04.jpg)

![Figure 5: Career anxiety x retrain type [by level of expertise]](/assets/individual/thinktank/assets/20240325_column_05.jpg)