What constitutes an approach to human resources management that promotes reskilling for workers?

Release Date:

※This article is a machine translation.

In recent years, Japanese companies have accelerated their efforts to reskill employees; however, companies remain very much at the stage of exploring options. We conducted a “quantitative survey on reskilling and unlearning” to ascertain the current state of reskilling and the human resource management factors that promote this state. In this column, we would like to explore specific ways to view the intersection of reskilling and human resource management (HRM) while referring to the results of this survey.

- Background to the Reskilling Boom

- The limitations of the current reskilling debate

- The Reality of Reskilling

- The relationship between reskilling and personnel systems and personnel management

- Reskilling and Managerial Management

- Summary

Background to the Reskilling Boom

Reskilling is currently attracting a great deal of attention. Every day, there are reports about the reskilling initiatives and results being promoted by companies. The background to this can be attributed to trends such as DX, the disclosure of human capital information, and the trend towards autonomous career development. Following the proposal of the “Reskilling Revolution” by the World Economic Forum in 2018, “reskilling” seems to have leapt to the center of trends in the labor world in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

However, if you look at the content of the reskilling debate in Japan in particular, it is not really anything new. The emphasis on investing in and developing people is an extension of the “humanism” management approach (Takayuki Itami) that began in the late 1980s, and since the bursting of the bubble economy, the need for adults to relearn has been pointed out time and time again, along with slogans such as “recurrent education”. There is also a simple “rehash” aspect that is common in the human resources industry.

Even so, if we were to point out the uniqueness of the current reskilling boom, it would be that, compared to “relearning”, the emphasis of reskilling has become clearer in that the driving force is on the side of “companies”. As traditional human resource development has merged with DX and been rebranded as “DX human resource development”, management decision-making has become more drastic. In fact, if you look at the content of corporate reskilling training, you will see words like “AI”, “machine learning” and “statistical analysis” appearing frequently.

The shortage of digital talent that cannot be solved through mid-career hiring can only be addressed by training people internally, and there will continue to be a need for people who can flexibly adapt to the ever-changing business environment. With the government also pushing for human resource investment in response to such corporate needs, the tide of Japan’s long-sluggish investment in human resource development is finally beginning to change.

The limitations of the current reskilling debate

However, when I look at the content of the reskilling debate, I often find myself tilting my head to the side. In recent decades, a great deal of knowledge has been rapidly accumulated in Japan regarding human resource development and human resource development, but as soon as the topics of “reskilling” and “human capital” are raised, the models of thought become strikingly simple, almost as if we have reverted to our ancestors.

Most of the reports and discussions about reskilling rely on a linear, simplistic model of “identifying necessary skills” → “acquiring new skills” → “matching with jobs (posts)”. If you superficially follow flashy overseas examples that involve large-scale job changes, you will naturally be drawn to this kind of thinking. It’s the old-fashioned “factory model” idea of creating a “mold” for the necessary skills, pouring the human resources into it, and then “shipping” them to where they are needed.

Of the three classic management resources – people, goods and money – it is people who have the greatest degree of “elasticity”. The range of abilities and skills that people can demonstrate depends greatly on the environment in which they find themselves. There are countless examples of people who join a company with a big fanfare as “industry professionals”, such as super engineers or experts in new business development, but then end up leaving because they are unable to function at all in their new company. The “environment dependence” and “context dependence” of human ability and skill demonstration are things that various social sciences have examined and proven from many different angles.

In other words, the problem with the “factory model” of the current general reskilling debate is that it is too simplistic in its perspective on the most important processes of “acquisition” and “demonstration” of skills. To begin with, the low motivation to learn and lack of learning habits among Japanese workers has been pointed out in various international surveys. Even if you create learning opportunities with the enthusiasm of “autonomous learning”, only a small percentage of employees will learn voluntarily. Also, even if you cram in “memory” and “knowledge” of technology in short-term intensive courses, training and seminars, there is still a long way to go before “demonstration”.

What is needed to expand this simple image of reskilling is a perspective (perspective) and vocabulary (vocabulary) that allow us to discuss the issue in a more realistic and detailed way. So, let’s look for some hints in the “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning” conducted by Persol Research and Consulting.

The Reality of Reskilling

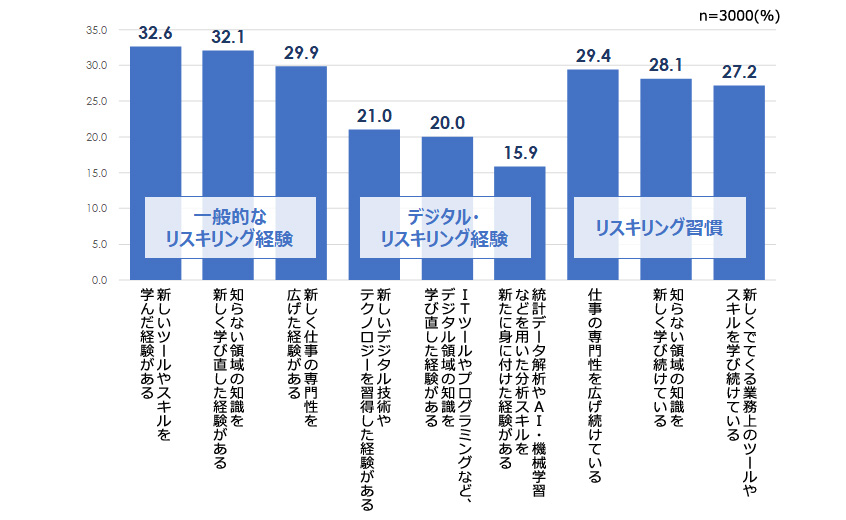

First, let’s take a simple look at the reality of reskilling among current workers, based on the data we have. Among all regular employees, around 30% have had “general reskilling experience”, and around 20% have had digital reskilling experience (digital reskilling experience), such as IT tools or statistical data analysis, which is emphasized these days. In addition, just under 30% of respondents said they had a “reskilling habit” of constantly learning new skills and tools (Figure 1). Although not a particularly high number, it is a realistic figure when you consider that there are often cross-departmental transfers and subsequent relearning through job rotation.

Figure 1: The reality of reskilling

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

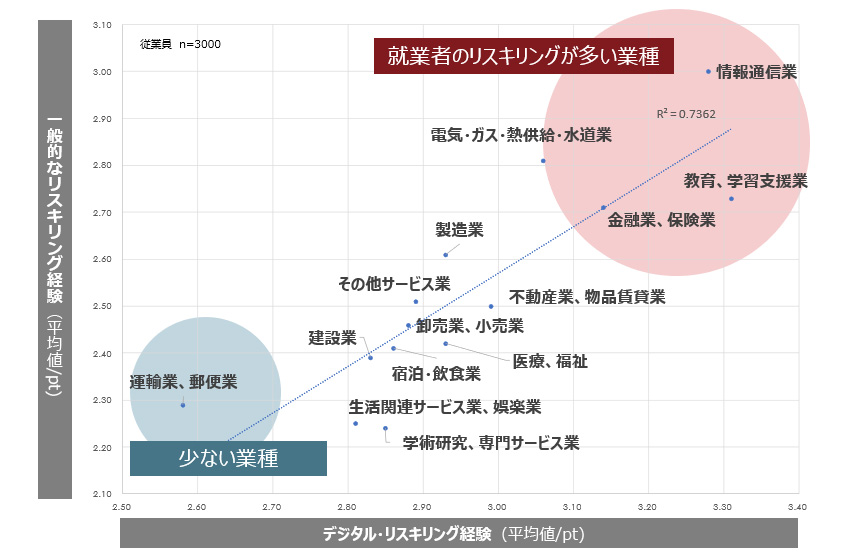

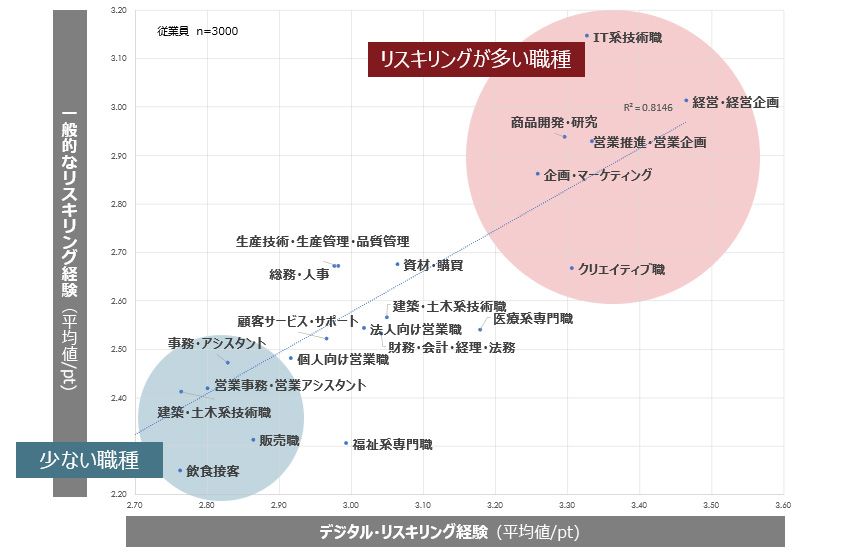

Figures 2 and 3 show the reskilling situation for workers in different industries and occupations, summarized

as a reskilling map.

Figure 2: Reskilling Map by Industry

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

Figure 3: Reskilling Map by Occupation

Source: Persol Research and Consulting ”Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

Looking at these, we can see that there is a strong correlation between reskilling in the digital domain and

more general reskilling experience. Some commentators have emphasized the difference between reskilling and

“learning again” in the past, but given the recent development of IT tools, it is only natural that some digital

element should be included in general reskilling, and it is probably not something that needs to be emphasized.

Looking at the map in Figure 2 by industry, the industries with the highest rate of workers who have undergone reskilling are “Information and communications”, “Education and learning support”, “Finance and insurance”, and “Electricity, gas, heat supply, and water supply”. These are probably industries that have been strongly affected by structural changes such as the need for DX and digitalization, and carbon neutrality. It could also be pointed out that these are industries that have been greatly affected by recent social changes due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The amount of experience with reskilling varies greatly depending on the type of job. “IT-related technical jobs”, “product development and research”, and “planning and marketing” are types of jobs that have a lot of experience with reskilling, but these types of jobs can also be summarized as jobs that are directly affected by (or require a response to) business changes. On the other hand, there is little experience of reskilling in the fields of “construction and civil engineering-related technical work”, “food and drink service”, “sales” and various “clerical and assistant” jobs. This “disparity” in reskilling by job type is a point that we will continue to pay attention to in the future, as it is directly linked to the disparity in adapting to changes in the labor market in the future.

The relationship between reskilling and personnel systems and personnel management

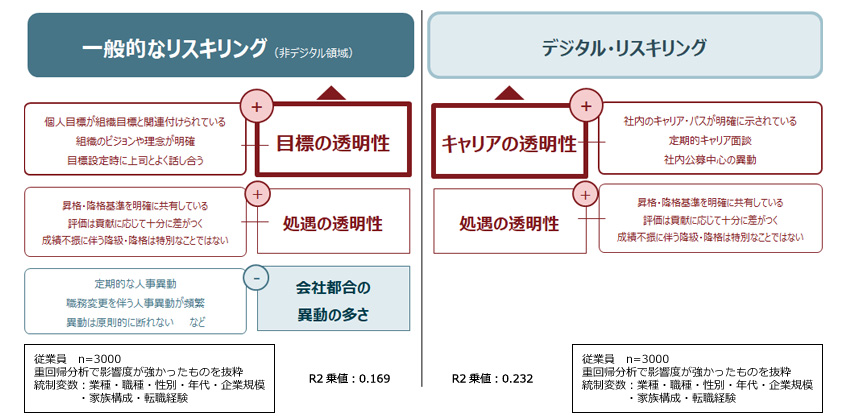

Now, let’s get down to the main topic. First, we looked at the relationship between the practice of reskilling

employees and the characteristics of overall human resource management.

Among the various elements of human

resource management, the one that is most closely linked to general reskilling in the broad sense is “goal

transparency”. This means that individual goals and organizational goals overlap.

The results of this are thought-provoking. This is because in many companies, goal management systems have become a mere formality, and many companies have not yet taken steps to reform or improve their systems. Although there is a lot of talk in the world about flashy system reforms such as “job-type employment”, the goal management and evaluation processes, which are the touchpoints between the actual personnel system and employees, continue to be secondary.

In addition, the fact that the evaluation and treatment processes are integrated in goal management is also a characteristic of many Japanese companies. It has also been found that the human resource evaluation system, which is based on relative evaluation and does not allow for extreme differences, inhibits the “unlearning” of individuals in order to promote reskilling. In the reskilling debate, which tends to be limited to “education”, target management is rarely discussed, but the results suggest that reviewing the daily target management process can also lead to reskilling. There is not enough space here to discuss the problems with and solutions for the target management system in detail, so please also refer to the separate column “What is Target Management that Develops People? The Key is the ‘Implicit Evaluation View’ of Employees”.

On the other hand, “career transparency” was most positively related to reskilling in the digital domain. In companies where internal career paths are clearly indicated, there are regular career consultations, and transfers are mainly based on internal job postings, employees are more likely to be reskilling in the digital domain. It seems that what is important in “DX human resource development”, which often assumes job changes, is that employees can see their “career” after learning.

Conversely, the large number of transfers carried out for “company reasons” has been seen to have a negative impact on reskilling. In the careers of Japanese companies, job transfers ordered by the company come first, and on-the-job training (OJT) led by the workplace, which involves adapting to the new situation, comes second. This is a kind of “review” style of learning. In contrast, the essence of learning in reskilling is in the “preparation” that anticipates the voluntary selection of future jobs. Repeated transfers that are not related to one’s own will due to company circumstances have kept workers in Japanese companies away from learning.

Figure 4: The relationship between reskilling and personnel systems and personnel management

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

Reskilling and Managerial Management

Another factor that I would like to mention is the “workplace”. The reason why many reskilling discussions seem like idealistic theories is that the “workplace” factor is being ignored due to the “factory model” concept mentioned above. Let’s take a look at the relationship between the actions of managers, who are important players in the workplace, and the reskilling of employees (subordinates).

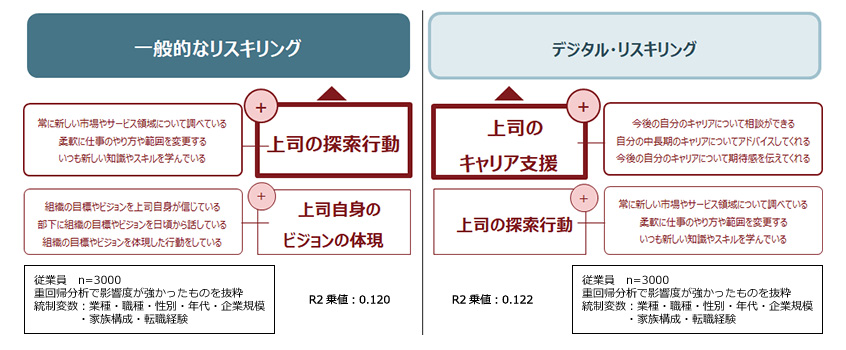

The factor that affected both general reskilling and digital reskilling was the “exploratory behavior” of the supervisor. When the supervisor shows a welcoming attitude towards new changes and is learning, this encourages subordinates to learn new things too. Conversely, when the supervisor does not like change, it seems that subordinates also do not try to promote reskilling. Previous research has also confirmed that managers’ change-oriented behavior promotes unlearning, and this can be seen as a stable trend.

※Mutsumi Matsuo, 2021, “Unlearning at Work”, Dobunkan Publishing

In addition to such exploratory behavior, “career support” by managers for their subordinates also has a positive impact on digital reskilling. Again, it seems that the “career” element is deeply involved in digital reskilling. Supervisors and subordinates should engage in dialogue about careers, communicating their expectations and hopes to each other and encouraging them to have a medium- to long-term vision. In many workplaces, dialogue about careers is given a low priority, but improvements are being sought under the name of “promoting career autonomy”.

Figure 5: The relationship between reskilling and manager management

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

Summary

In this column, we have looked at the content of human resources policies and manager management related to reskilling based on our own quantitative analysis. Even just looking at the relationship with overall human resources management, you can see that reskilling employees is an area that goes far beyond simply ‘providing training and education’. At the same time, the naivety of the simple model described at the beginning of this article – “identify necessary skills” → “acquire new skills” → “match with job” – is also highlighted. Human resource management is not a mechanical process of “strengthening” characters and “deploying” them on the battlefield, like in a war simulation game, but an organic process involving many interrelated elements.

Among the various elements that seem to be involved, “optimizing goal management”, “transparency of career paths”, and “promoting dialogue between superiors and subordinates regarding careers” have emerged statistically as elements that may be prioritized over others. I hope that this paper will be of some help in considering how to prioritize and implement measures.

THEME

注目のテーマ

CONTACT US

お問い合わせ

こちらのフォームからお問い合わせいただけます