What are the “three types of learning behavior” supporting the reskilling of workers?

Release Date:

※This article is a machine translation.

Reskilling initiatives are accelerating. However, the term reskilling is abstract and can sometimes lack in on-the-ground reality when it comes to discussions about policy or management. We conducted a quantitative survey on reskilling entitled “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning.” We would like to introduce data on the three specific types of learning behavior related to reskilling as obtained through this survey and raise the level of discussion on this topic.

- The “reskilling” debate rings hollow

- Three learning behaviors that support reskilling

- Why is reskilling difficult for middle-aged and older workers?

- Summary: Reskilling is about promoting the “emergence” of skills

The “reskilling” debate rings hollow

At the moment, there is a lot of discussion about “reskilling” going on in many different places. Initiatives are being stepped up, particularly by major companies, and there is also an increase in media coverage, while the government is also showing signs of further boosting investment in human resources by companies. The term “reskilling” is now so common that it is hard to go a day without hearing it in the human resources development and human resource management (HRM) industries, but this concept is not one that was originally used in academic research, but rather a general term that was proposed at the Davos Conference in 2018 and has since spread. As a result, the definition is rather loose, and it is already widely used to mean something like “acquiring (having someone acquire) new skills”.

However, perhaps because of its abstract and broad meaning, the discussion of reskilling often becomes something that can only be called an impractical discussion. Most of the reports and discussions about reskilling have a linear and simplistic idea of “identifying necessary skills” → “acquiring new skills” → “matching with jobs (posts)”. In an era of rapid change, it is understandable that people are acquiring new skills, particularly in the digital domain, in preparation for the job changes that lie ahead, but it doesn’t really add anything new to the traditional topic of learning in the working world, and it doesn’t seem to make use of the many social scientific findings that have been accumulated to date in relation to learning.

Furthermore, the current concept of “reskilling” is linked to the even more confusing buzzword “DX (digital transformation)”. In order to reskill, it is said that “it is necessary to first clarify the DX strategy” and “to clarify the image of DX human resources”. However, at this point, the discussion of reskilling almost falls into “textbook-like niceties”. The reality is that few Japanese companies have a DX strategy that is specific enough to clearly define the required headcount and even fewer have a clear idea of the skills required at a technical level. It would be quite a challenge to expect companies that are still groping their way forward to take on this extremely innovative management task of developing a business model that makes use of digital technology in a non-linear way.

On the other hand, it is still possible to lower the level of abstraction of “reskilling” and break it down into more concrete employee actions. If we can make the discussion of reskilling, which is often summarized in terms such as “relearning” and “reacquiring skills”, more granular and realistic, we may be able to find hints for many measures.

Therefore, Persol Research and Consulting conducted a quantitative survey to explore more specific learning behaviors related to reskilling.

Three learning behaviors that support reskilling

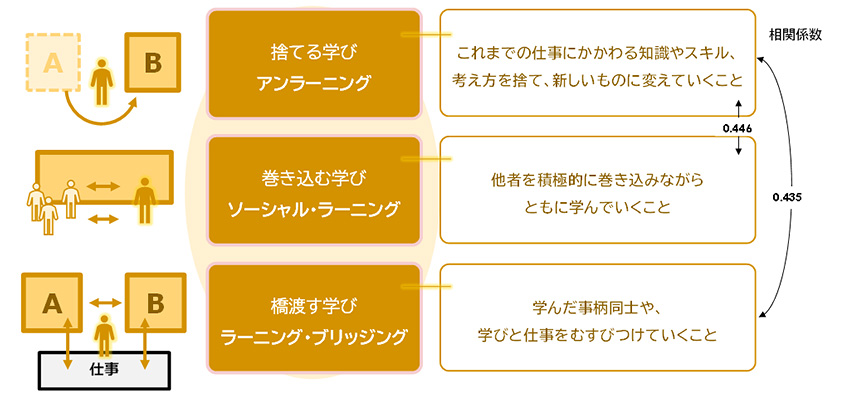

In this survey, three more specific learning behaviors related to reskilling were identified. These are the three behaviors of “unlearning,” “social learning,” and “learning bridging” (Figure 1).

As a result of an analysis that controlled for basic attributes, it was confirmed that these types of learning have a positive relationship with reskilling. These can be organized as learning behaviors at a concrete level that support the ambiguous and broad concept of reskilling. Of course, this is not the only important factor, but it is useful for making the granularity of the discussion of reskilling more detailed.

The first of these, ‘unlearning’, is a concept for which research findings have been accumulating, and so we have already discussed it in the column “What prevents workers from unlearning?”. Unlearning is, in plain terms, the action of ‘discarding old ways of doing things in order to acquire new ways of doing work and new skills’. It is a more dynamic and dynamic concept that focuses on “rejecting” what you have learned in the past and the work know-how you have used up to now, rather than simply acquiring new skills. As introduced in the column “What prevents workers from unlearning?”, the experience of “perceiving one’s limitations” when you realize that you can’t exert your influence in your current job promotes unlearning.

*The concepts of “social learning” and “learning bridging” were derived from a joint research project (the “Learning and Happiness” Research Lab for People in Their Twenties) conducted by Benesse Educational Research and Development Institute, Rikkyo University Professor Jun Nakahara, and Persol Research and Consulting. For more information, please see the special website “Learning and Happiness” Research Lab for People in Their Twenties.

Figure 1: The three types of learning that support reskilling for workers

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning”

The second concept, ‘social learning’, can be summed up as ‘involving others in learning’. Specifically, it is

the act of actively involving others in one’s own learning and study, such as ‘getting opinions from the people

around you’ or ‘going to talk to experts or people who know a lot about the subject’.

As is well known from the work of Raye and Wenger on “legitimate peripheral participation”, the idea that people learn through others has long been a focus of learning research. Data analysis has also shown that experiences outside the workplace, such as commuting to graduate school, off-the-job training, and moonlighting, promote this social learning. Transnational experiences are connected to relationships with people other than one’s usual colleagues and superiors, and this kind of “involvement” is probably happening.

At present, many companies are revamping and evolving their training systems as “corporate universities” as part of their reskilling practices. The specific details of these vary widely, but many companies are gathering lecturers from within the company and preparing a wide range of courses, from work know-how to mindset. If these in-house universities function as “communities of learning” in the same way as actual universities, they will become places for social learning in their own right. The skill of corporate human resources aiming to reskill will be shown in how they can spread this “involvement” both inside and outside the company throughout the whole organization.

The third concept, “learning bridging”, is about “bridging learning”. It is about linking work experience with what you have learned, and using the knowledge you have gained in your work. It is about bridging knowledge with practice.

At first glance, this seems like a very difficult thing to do. In David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, it refers to the abstract practice of linking “reflection”, “conceptualization” and the next stage of “practice (experimentation)”.

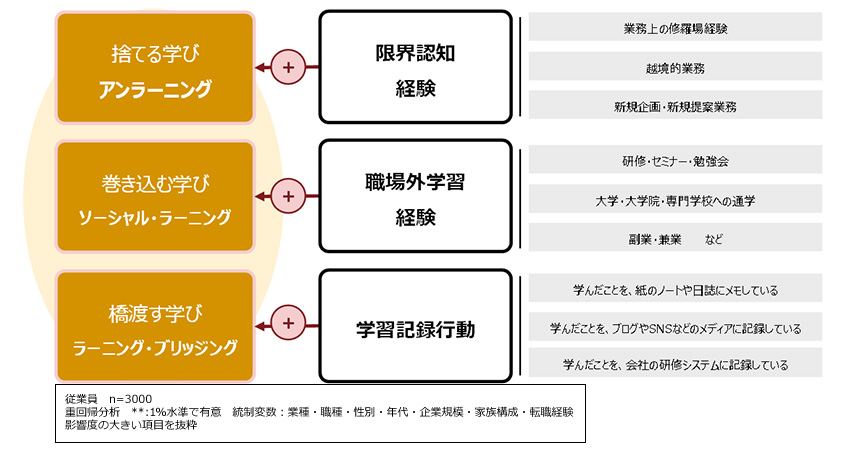

However, there are some hints. From this survey, we learned that keeping a record of personal learning in a notebook or blog, or in other words, practicing “learning logs”, was positively related to learning bridging.

Any training or education is meaningless if it doesn’t lead to changes in work, and it is especially difficult for white-collar workers to acquire skills through physical repetition. There are limits to the knowledge that can be remembered. No matter how much knowledge you gain through training or self-study, it will be reset as soon as you return to the workplace. This process of forgetting is the “great enemy” of reskilling.

If we draw a conclusion from the data we have just looked at, it seems that we can promote learning bridging by recording knowledge and skills that are forgotten as short-term memory as “stock”. The support for “externalizing memory ≈ recording learning” to promote bridging, such as the history function of learning management systems, follow-up after training, and the design of training with a time gap, is an area where many ideas can be used with various tools.

Figure 2: The three types of learning, behavior, and experience that support “reskilling

Source: Persol Research and Consulting ”Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning

Why is reskilling difficult for middle-aged and older workers?

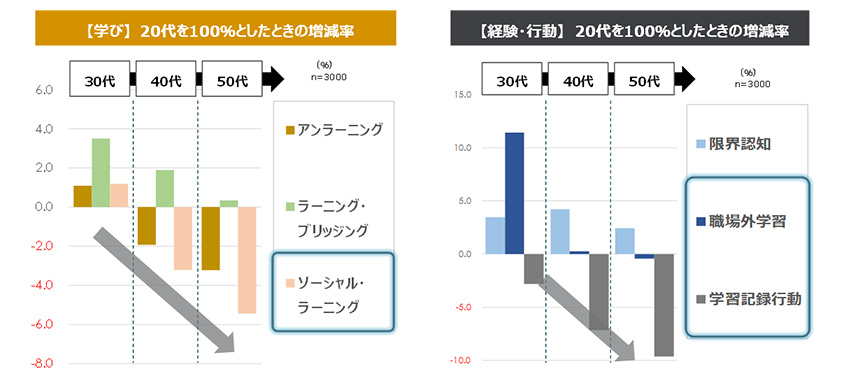

Now we have looked at the three learning behaviors. By breaking down the elements in this way, we can learn more about the highly abstract concept of “reskilling”. For example, when we look at these behaviors by age group, it becomes clear why reskilling is difficult for middle-aged and older workers. As shown in Figure 3, we can see that all three learning characteristics related to reskilling tend to decline in the 40-50 age group. Furthermore, two of the behaviors and experiences that promote learning – “learning record behavior” and “learning outside the workplace” – have fallen significantly in the 40-50 age group.

Figure 3: Changes in the three learning characteristics and the three behaviors and experiences that promote learning (by age group)

Source: Persol Research and Consulting “Quantitative Survey on Reskilling and Unlearning

Companies that feel that reskilling middle-aged and older employees is an issue will find it helpful to

encourage these experiences. Rather than preparing a wide range of e-learning courses and lamenting that “the people

we want to learn aren’t learning”, it should be possible to make reskilling middle-aged and older employees more

accessible by actively assigning them cross-border work experience and making various innovations, such as combining

training with a range of recording tools.

Summary: Reskilling is about promoting the “emergence” of skills

We have introduced three types of learning related to reskilling: unlearning, social learning and learning bridging. Findings from past learning theories and cognitive science have made it clear that the image of learning as “injecting” skills into people like a vaccine is simply wrong.

The kind of learning that supports reskilling is “involving people, connecting knowledge and experience, and discarding old ways of doing things to create new practices”. In addition, the “environment” of work experience and records of learning outside the workplace promoted such learning behavior. Of course, not all of the important elements have been exhausted, but by breaking down the elements in this way, it becomes clear that reskilling is a “emergent” activity that occurs between the environment and the individual.

Just as cramming education is often criticized, focusing too much on the “input” of education does not lead to the concrete “output” of demonstrating skills in the workplace. No matter how much “reskilling” is done, which lacks social learning, unlearning, and learning bridging, it will end up as nothing more than the provider’s self-satisfaction.

What companies that want to promote reskilling should do is not to cram training into their employees and inject skills into them. Rather, they should develop their corporate environment and systems so as to maximize the process of “emergence” of skills and practices as described above. This column has only been able to introduce a limited amount of data, but I hope it will provide some hints for “emergent” reskilling.

THEME

注目のテーマ

CONTACT US

お問い合わせ

こちらのフォームからお問い合わせいただけます