How should we deal with the massive retirement reserve force that is coming in a few years? How should we prepare for and support progress in terms of post-retirement reemployment?

Release Date: Update Date:

※This article is a machine translation.

The theme for this issue is “post-retirement reemployment”.

The 2013 revision of the Act on

the Stabilization of the Employment of Elderly Persons mandated that companies provide employment opportunities for

their workers until the age of 65 years. As of 2017, 99.7% of all employers had secured such employment

opportunities for their workers until the age of 65 years. On the other hand, 77.7% of all companies maintain a

retirement age of 60 years. (Note 1) In other words, a majority of companies have made it customary to conclude

reemployment agreements annually with workers between the ages of 60 years and 65 years in what is referred to as

the so-called post-retirement reemployment. In this paper, the keys to understanding the changes and progress

concerning individuals working before and after post-retirement reemployment shall be explained.

In the “Project to Explore

Breakthroughs from Middle-Aged Workers”,

the definition of “middle-aged” and “senior” is as follows:

[middle-aged: 40 to 54 years old] [senior: 55 to 69 years old]

In our “Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Career Advancement Survey” of 2,300 middle-aged and senior workers in their 40s to 60s, it was revealed that more than half (57.3%) of senior workers hope to be re-employed at their current workplace, and that only around one in five (19.7%) are considering complete retirement. Considering the current situation with Japan’s social security system, such as the increase in the pension eligibility age, it is expected that the number of people choosing to continue working after retirement will continue to increase.

For companies too, the debate surrounding the re-employment of senior employees who have reached retirement age is becoming an important management issue. In particular, the large number of employees from the bubble generation (those who joined companies as new graduates between 1986 and 1991) who were hired in large numbers during the bubble economy will reach 60 years of age within the next 10 years, and the resulting rise in personnel costs associated with re-employment after retirement will have a significant impact on business that cannot be ignored. However, most of the human resources measures for the employment and working styles of senior workers through re-employment after retirement are only symptomatic measures in line with the implementation of legal revisions, and the current situation is that they have not yet reached the point of reviewing systems and improving the working environment with an eye to making breakthroughs.

In an unprecedented era of labor shortages, when the number of people short of labor, which was 1.21 million in 2017, is expected to reach approximately 6.44 million by 2030 [Note 2], it is clear that we need to take steps as soon as possible to encourage the advancement of senior employees who have reached retirement age, not as a source of cheap labor, but as a source of competitive advantage that creates value.

In this report, we will consider the question of how companies should approach employment and human resources utilization in the face of the large number of workers who will be approaching retirement age and looking for re-employment within the next few years, using the results of a large-scale survey of middle-aged and senior workers conducted in collaboration with the Ishiyama Nobutaka Laboratory at Hosei Graduate School as a guide.

- Changes in re-employment after retirement – “The work I am in charge of does not change, but my salary decreases significantly”

- Preparing for re-employment after retirement – “The importance of expertise” only realized after re-employment

- Changes in attitudes towards re-employment after retirement – around 40% are dissatisfied with pay cuts, resulting in a drop in motivation

- Satisfaction with re-employment after retirement: Satisfaction with the company, work and workplace is high, but dissatisfaction with salary is noticeable

- The key to making a breakthrough in re-employment after retirement is “offering treatment that matches the work content”

1. Changes in re-employment after retirement – “The work I am in charge of does not change, but my salary decreases significantly”

First, let’s take a look at what kind of changes are occurring for individuals who are rehired after retirement.

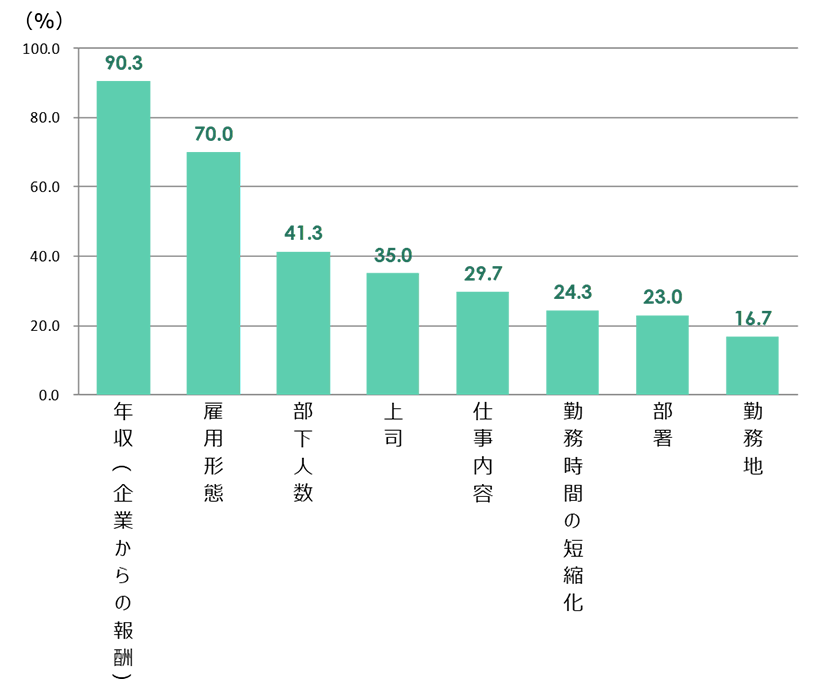

According to our survey, we found that over 90% of people experienced a change in their annual income [Figure 1].

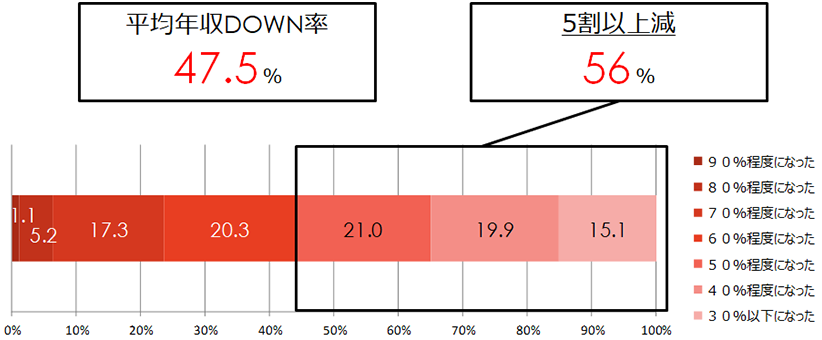

When we looked at the change in annual income in more detail, we found that the average decrease in annual income

was 47.5% compared to just before the switch to rehiring after retirement, and that over half of all respondents

answered that their income had decreased by over 50% [Figure 2].

If we look at it straightforwardly, we can

assume that this result is due to the fact that the content of the work they are in charge of has changed

significantly in their post-retirement reemployment. However, contrary to this expectation, the results show that

only just under 30% of people have seen a change in the nature of their work since being re-employed after

retirement【Figure 1】. In other words, the trend in Japanese companies for re-employment after retirement is

characterized by “a significant drop in salary despite no change in the work assigned”. This result

can be seen as reflecting the impact of Japanese employment practices, where wages are determined by seniority-based

pay, rather than by the content of the work or the results of that work.

Figure 1: Changes in work content after re-employment after retirement (unit: %)

The

vertical axis shows the percentage of respondents who answered “yes”.

The

vertical axis shows the percentage of respondents who answered “yes”.

Figure 2: Percentage decrease in annual income after re-employment after retirement (unit: %)

2. Preparing for re-employment after retirement – “The importance of expertise” only realized after re-employment

So, what kind of image did senior workers have of their post-retirement reemployment career and working style, and

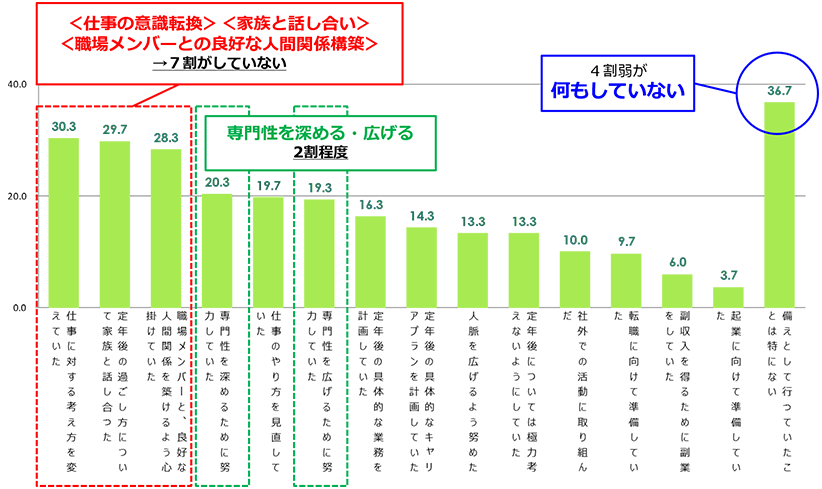

to what extent did they prepare for it? When we asked about “preparations made before retirement”, the

largest group was those who said they had not made any preparations, and around 40% of the total answered that

they had not done anything in particular to prepare for it [Figure 3].

This tendency not to make

preparations in advance is not limited to re-employment after retirement. The same tendency not to make preparations

in advance is also seen in the “changes after mandatory retirement from a position” discussed in the previous report

“The reality of the operation of the

‘mandatory retirement from a position’ system, and its merits and demerits”. It could be suggested that, after

a long period of time has passed without making proactive decisions about one’s own career, while leaving career

ownership in the hands of the company in exchange for long-term employment security, it becomes difficult to detect

changes in the environment that are approaching oneself in advance and to adapt flexibly.

On the other hand,

the results for the content of preparations made in advance showed that the top priorities were related to work

attitudes and human relations, such as “reviewing one’s attitude towards work” (30.3%), “discussions with family

members” (29.7%), and “building good relationships with colleagues” (28.3%). In addition, the proportion of people

who were making efforts to improve their work-related expertise was not particularly high, at around 20%. However,

the survey results for “things I should have done before retirement” show that “expanding my expertise” and

“deepening my expertise” came in second and third place respectively, suggesting that “work expertise” has the

characteristic of only being recognized as important when re-employed after retirement.

What does this mean? As we will see later, it is clear that those who are more aware of the social contribution and significance of their work, and those who feel they are growing in their work, are the ones who are more active in their 60s [Figure 6]. In other words, by becoming a re-employed employee after retirement, you can focus on your social contribution and growth through your work as an individual and titles, and by focusing on their own social contribution and growth through work as an individual, they may become aware of what they can do and what they want to do, and recognize the importance of improving their work expertise.

Figure 3: Preparations for re-employment after retirement

The vertical axis shows the

percentage of respondents who answered “yes”.

The vertical axis shows the

percentage of respondents who answered “yes”.

3. Changes in attitudes towards re-employment after retirement – around 40% are dissatisfied with pay cuts, resulting in a drop in motivation

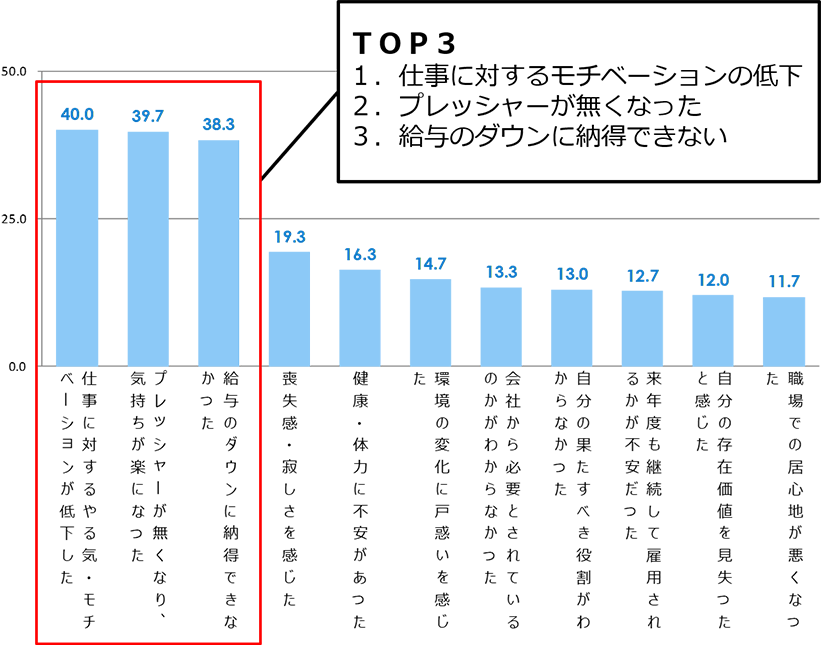

Next, what kind of psychological changes occur in people who have experienced re-employment after retirement? As a

result of investigating changes in attitudes towards re-employment after retirement, an interesting discovery was

that the negative response of “motivation and motivation towards work decreased” and the positive response of “I

felt relieved because the pressure was gone” were both around 40%, almost the same level.

In addition, around

40% of respondents also said that they “could not accept the pay cut”. As we have seen, these results reflect

dissatisfaction with the irrational human resource management of re-employment after retirement, where “annual

income decreases significantly even though the nature of work has not changed”.

Figure 4: Changes in attitudes towards re-employment after retirement

The vertical axis

shows the percentage of respondents who answered “this applies to me”.

The vertical axis

shows the percentage of respondents who answered “this applies to me”.

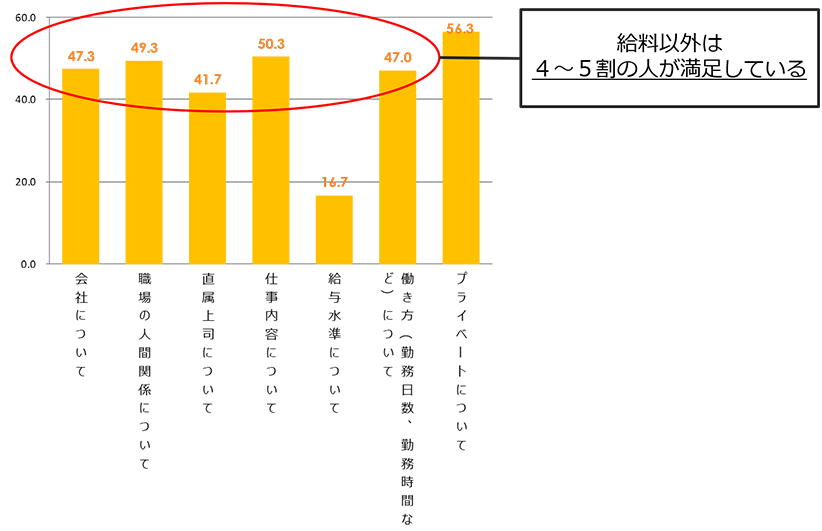

4. Satisfaction with re-employment after retirement: Satisfaction with the company, work and workplace is high, but dissatisfaction with salary is noticeable

When we surveyed satisfaction with re-employment after retirement, we found that around half of the respondents

were satisfied with the content of their work and their workplace relationships【Figure 5】 On the other hand,

satisfaction with pay levels was extremely low, with less than 20% of the total respondents satisfied. As with the

data we have seen so far, this result can also be seen as a sign of dissatisfaction with not being paid commensurate

with the work content.

The comment “I’m fed up with being asked to produce the same output as before for a low

salary even after I retire” (male, 61, manufacturing industry/production engineering/production control) suggests

that there is also a significant mismatch between the level of results expected of them and the results they are

able to achieve.

Needless to say, job satisfaction is an important factor that affects work performance. For

Japanese companies, where the urgent management issue is to increase the productivity of re-employed workers after

retirement, the low level of satisfaction with salary levels must be seen as a result that cannot be

ignored.

Figure 5: Satisfaction after retirement

The vertical axis shows the percentage of

respondents who answered “yes”.

The vertical axis shows the percentage of

respondents who answered “yes”.

5. The key to making a breakthrough in re-employment after retirement is “offering treatment that matches the work content”

Up to this point, we have looked at the changes that occur before and after post-retirement reemployment, as well

as the reality of the preparations made in advance for post-retirement reemployment. So, what characteristics do the

60-year-olds who are making a breakthrough in post-retirement reemployment have?

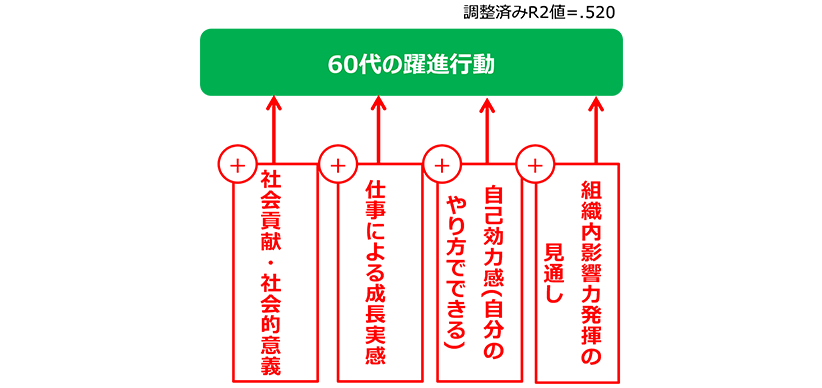

As a result of the analysis,

four common trends in work views and career awareness were identified: (1) “I am doing work that is useful

to society”, (2) “I feel I am growing through my current work”, (3) “I am doing my work in my own way”, and (4) “I

am able to exert influence on the organization”.

The second point that we would like to draw your

attention to here is “the sense of growth through work”. In discussions about the re-employment of

employees after retirement, the focus tends to be on “utilizing expertise”, such as how to make the most of the

knowledge and skills that have been cultivated up to now, and how to pass them on to the next generation.

However, the results of this analysis show that the key to the success of re-employed workers after

retirement is not the “demonstration” of their expertise, but rather “further improvement” (i.e. growth).

Do

you see middle-aged and senior workers in their 60s who have reached retirement age as “human resources whose

growth has already stopped,” or do you see them as “human resources who can continue to grow in the future”? Isn’t

this a question that everyone involved in the management of re-employed employees after retirement should stop and

ask themselves?

【Figure 6】 Factors that influence the actions of people in their 60s

※Only items that

meet the statistical significance level (p<.05) are shown

※Only items that

meet the statistical significance level (p<.05) are shown

In addition, the four characteristics introduced here are only the main points when looking at the internal aspects of individuals, such as their work views and career awareness, and it is not possible to discuss their importance without taking into account the influence of external environmental factors such as salary levels.

As the debate over further extending the retirement age and abolishing the retirement age becomes more realistic, the improvement of productivity among employees who are re-employed after retirement will become an even more important management issue than it has been up to now. One suggestion that can be drawn from the results of this survey is to “evaluate job expertise and offer compensation that is commensurate with the work content (and results)”. This will not only remedy the low level of satisfaction with salary levels, but it is also expected to increase the number of senior employees who are more oriented towards growth through their work.

Of course, it is also expected that improvements in compensation will lead to an increase in personnel costs. However, at a time when the cost of hiring new staff is increasing due to a serious shortage of manpower, maximizing the performance of existing employees is something that should be considered, even if it means accepting a certain increase in personnel costs. It is time to reconsider the current drastic measures of cutting personnel costs, which have ballooned due to the aging population, by means of mandatory retirement (post-off) and re-employment after mandatory retirement. I think that we need to have discussions in the future about the premise that people can continue to grow even as they age, and that by positioning personnel costs as an “investment” rather than a “cost” and providing remuneration in line with performance, we can raise engagement with work and the organization and ultimately improve productivity, and that we should put in place a system of evaluation and remuneration for middle-aged and senior workers that is based on their level of growth and performance.

Note 1: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Employment Status of Older Persons” 2017

Note 2: Persol

Research and Consulting and Chuo University, “Labor Market Projections to 2030”

Survey Overview

| Persol Research and Consulting / Hosei University Ishiyama Laboratory ”Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Advancement Survey” |

|

|---|---|

| Survey Method | Internet survey using survey company monitors |

| Survey participants | 2,300 businesspeople who meet the following requirements (1) Men and women aged 40 to 69 who work for companies with 300 or more employees (2) Full-time employees (including those rehired after retirement in their 60s) |

| Survey period | May 12th – 14th, 2017 |

| Survey implementer | Persol Research and Consulting Co., Ltd. / Ishiyama Laboratory, Hosei University |

When quoting, please clearly indicate the source.

Example of source citation: Persol Research and Consulting

Co., Ltd. / Ishiyama Laboratory, Hosei University “Middle-aged and Senior Workers’ Advancement Survey”

THEME

注目のテーマ

CONTACT US

お問い合わせ

こちらのフォームからお問い合わせいただけます